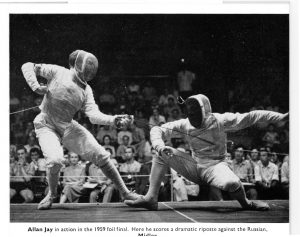

In memory of the late Allan Jay, we remember his life and fencing career, as told by Malcolm Fare.

Allan Louis Neville Jay MBE, who has died at the age of 91, was one of Britain’s greatest fencers, winning the world foil championship in 1959 and the next day just missing the epee title by one hit. The following year at the 1960 Rome Olympics he won silver medals in both the individual and team epee events, missing the individual gold only after a barrage with Italy’s Giuseppe Delfino, but gaining some compensation by beating the Italian in the team event.

Jay fenced in five Olympics from 1952 to 1968, coming 4th in the individual foil in 1956, and represented Britain at eight world championships between 1953 and 1969, winning the individual foil bronze medal in 1957; in addition he collected a foil team bronze in 1955, an epee team bronze in 1957 and an epee team silver in 1965.

His international success began in 1950, when he was in the Australian epee team that won gold at the British Empire Games. The following year he was runner-up in the World Student Games at foil, a performance he repeated twice at epee (1953 & 54). At foil he won his first world championship medal in 1955 as a member of the team that came third in Rome, and in the same year was runner-up in the Budapest tournament. In 1957 he was the winner in Ghent and won an individual bronze medal at the world championships in Paris, coming second in the Duval and Martini tournaments the following year. He went on to win at Evreux (1960), was runner-up in Budapest (1962), won the Duval (1963) and came second in Antwerp (1970).

At epee he won Noordwyck twice (1955 & 1957), came 5th in the 1957 world championships when he also won a bronze medal in the team event, was runner-up in Luxembourg (1958), won in Amsterdam (1959) and Mondorf (1964), came second in the London Martini (1965) and was a member of the silver-medal winning team at the 1965 world championships.

He was Commonwealth foil champion in 1966, having been the silver medallist four years earlier. In the British championships, he won the foil title in 1963 and was runner-up five times; at epee he was first, second or third every year for the nine years 1952-1960, becoming champion three times (1952, 1959 & 1960) and runner-up five times.

Jay started fencing at Cheltenham School in the summer term of 1946 under an ex-army coach, Jock Reardon. The following year he met Bill Hoskyns for the first time at the Public Schools Junior Foil Championship in which Bill came third and Allan fourth. At the age of 17, he moved with his family to Australia and joined the Sydney Swords Club, winning his first trophy by becoming best Man-at-Arms. In the first New South Wales championships of 1949 he came second at epee, repeating this result in the national championship. He was resident in Australia just long enough to qualify for that country’s 1950 Empire Games team in Auckland, New Zealand. Although none of the team had seen an electric epee until 10 days before the event, they won the team epee title, much to the irritation of the England captain, Charles de Beaumont.

Jay stayed in Australia only 20 months before his family returned to England. He joined Salle Paul and in 1951 went to Oxford where Bill Hoskyns was a year ahead of him. The following year he won his British colours by fencing against Belgium at epee and against France at foil in two pre-Olympic training matches, beating Christian D’Oriola for the only time in his career.

Then began a period of friendship and intense rivalry with Bill Hoskyns. In 1951 Jay won the junior epee championship, Hoskyns won it the following year, as well as the junior foil title, with Jay in third place, and in 1953 Jay won the junior sabre championship, with Hoskyns second. Allan remembered that their successes seemed to run in six-monthly cycles, with himself winning more often between January and June, whereas Bill tended to do better from July to December.

Between them, they reached the final of most international foil and epee tournaments in the decade 1955-65, often flying to events in Bill’s single-engine plane. In 1956 they and Gillian Sheen created a sensation by becoming the first civilians to fly into Budapest since the war. Jay remembered squeezing into the plane through a tiny door no bigger than a cupboard and sitting with hands clenched and sweating profusely throughout the flight. Years later, he pointed out to Bill that, had the engine failed, Britain would have had no senior world or Olympic champions.

1956 was also the year he won the Epee Club Cup after a barrage with Bill and Brian Howes. The following year he was not invited to take part, after writing a critical article in The Star newspaper on the Epee Club. Jay believed the Club was failing to make the best use of the Cup as a training opportunity for the British national team, but Club president Luke Fildes said that was not the purpose for which the Cup had been presented.

Jay always claimed that he was blackballed from membership to the Club because he was a Jew rather than his criticism of team selection policy. When the Club invited him to join in 1958, seven years after he had won the junior British championship, he declined, replying that the pleasure of the anticipated invitation many years earlier had had ample time to dissipate. He did eventually agree to join in 1985, having won the British title twice in the interval.

Jay faced an agonising dilemma in 1958 when, at the top of his form having come 3rd in the 1957 world foil championship and 5th in the epee, he had to choose between training for the 1958 championships or studying for his law finals. He chose the law, qualified as a solicitor and sent Bill Hoskyns, who had just become world epee champion in Philadelphia, a telegram saying: “Green with envy – congratulations.” Perhaps that made him all the more determined to do well the following year, when he won the foil title and came second at epee. Hoskyns replied, “Repaid with interest.”

The fight off for the 1959 title in Budapest was a three-way barrage between Jay, Midler (USSR) and Netter (FRA). Jay beat Midler 5-3 and then led 4-1 against Netter. But he lost concentration and the score crept up to 4-all. Charles de Beaumont reporting in The Sword said: “Amid intense excitement Jay was driven remorselessly back to the warning line – and beyond until his rear foot was well over the back line. At that agonising moment Netter launched his attack, Allan parried quarte and won the bout and the title with a superb fleche riposte by disengagement.”

The following day he came second in the epee world championship, an extraordinary achievement, losing by one hit to Khabarov (USSR). He was particularly formidable in fleches and broken-time attacks, both unleashed at tremendous speed. His strong personality was a great asset. In his book Olympic Diary – Rome 1960, Neil Allen observed, “He is as dominating as an actor-manager once he is on the piste, but he is also a fighter.” His style was described by Feré Rentoul in The Sword: “He positively radiates strength, confidence, courage and determination; what he lacks in technique (which is not much), is amply made up by his ability to think and to outlast his opponent by sheer stamina. Perhaps more than anyone else among British foilists, Allan Jay has taken to heart Emrys Lloyd’s recipe of starting a fight as if the score were already 4-4.”

Following his 1959 triumph, there was a glorious period of five days when Great Britain held more Olympic and world individual titles than any other country: Gillian Sheen, Olympic foil champion, Bill Hoskyns, world epee champion, and Allan Jay, world foil champion. To complete a wonderful year, Allan married Carole, a marriage that lasted for the rest of his life – 64 years.

In total, Jay won an astonishing 153 competitions at foil and epee. In 1957 he became the first person to be awarded the AFA silver medal, for consistent final places in major tournaments and two years later he received the Association’s gold medal for winning the foil world championship. In 1971 he received the MBE and in 1983, like Bill Hoskyns, he became a vice-president of the Association.

If 1959 was his best year, 1972 was his worst, when he was not selected for a sixth Olympic Games. The team captain and chief selector, Gordon Signy, was seriously ill in hospital and the meeting to pick the team was going to be held at his bedside. But he died just before the appointed time and a decision was made to exclude Jay. He confessed later that such was his disappointment that he momentarily contemplated suicide and did not sleep properly for 2 years.

After his fencing career was over, he spent 15 years on various AFA committees, 10 years as honorary legal adviser, followed by 15 years as team manager, which gave him joy and aggravation in equal measure. He recalled an incident at the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984 when, as team manager, he was told that only five officials from each sport would be allowed to march in the opening ceremony. So he suggested to Dick Palmer, BOA General Secretary, that the rumour should be leaked to the organisers that the officials taking part would be wearing a black arm band in sympathy for their neglected colleagues. Suffice it to say that they all marched. Above all, British teams appreciated one gesture that he arranged whenever they were fencing in a capital city – a reception at the British embassy.

Jay held forthright views about people in the upper echelons of the fencing world. He regarded Mary Glen Haig as an excellent president of the Ladies Amateur Fencing Union and a good president of the Association, but thought her manipulative and utterly unscrupulous in achieving her ends. At the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, he was put forward for the position of vice-chairman of the BOA by the weightlifting chairman Wally Hammond, supported by Dick Palmer. Jay then wrote to Mary asking for her endorsement, but did not receive it and took his case to the BFA Board. Asked to leave while they discussed the matter, he could not resist listening at the door and heard Mary’s disparaging comments about him as a lightweight who didn’t know what he was doing, adding that weightlifting had withdrawn its support, so the Board decided not to endorse his application. Apparently she had phoned Hammond and said that Nick Halsted, then president of the BFA, was against Jay’s appointment, which was not true. Jay always felt that Mary could not tolerate a rival fencing centre of attention within the BOA. He also believed that it was Mary’s veto that prevented him receiving a national honour higher than MBE in recognition of his work for fencing.

But as well as being difficult and prickly, he could be kind and thoughtful. When two Sussex House stars, Khaled Beydoun and Paul Walsh, reached the final of the junior foil world championship, he wrote a congratulatory letter to each and enclosed £50. But when he received no acknowledgement, he made it known to their coach that they could keep the congratulations but he expected his money back. Two thank-you letters promptly arrived.

In 1996 Allan Jay was elected to the FIE Congress and served on various commissions until 2012. That year Shirley Netherway, a former Olympic fencer and long-time friend, wrote to the BFA Board recommending that he be honoured with an OBE in recognition of his 55 years of service to fencing. Nothing came of it. Instead another slight: he expected to be re-elected to the FIE Disciplinary Commission on which he had served since 2000, but his name was not put forward by the BFA, leaving Britain without a candidate. Shocked and hurt by the decision, he resigned from his last administrative position with the Association.

But he continued fencing and at the age of 82, after several years of driving each week from his home in Somerset to Bristol for bouts of sabre, he decided to return to his first love and took his first foil lesson for 40 years. But he was a terrible driver and wrote off three cars in three years. On one occasion he rang home to ask his wife Carole to collect him. When she asked where he was, he replied, “In the back of a police car.” On his way through a nearby village he had apparently driven over two ‘sleeping policemen’ and demolished an illuminated sign, plunging the village into darkness.

In later years, following a fall, he developed Alzheimer’s disease and found it difficult to speak or react to people. But Carole visited him every day and found an infallible way to communicate: she would say briskly “On guard” and he would respond to her attack with an immediate parry-riposte.

Allan Jay is survived by his wife, two daughters, Georgina and Felicity, and a granddaughter, Amber.

Provided by Malcolm Fare.

Sign up to receive regular highlights from the exciting world of fencing - celebrating the best of our unique and inspiring community