As part of a series of articles for coaches and members interested in coaching, Siân Hughes Pollitt speaks with Head of Pathways Steve Kemp on plotting your course, climbing your Everest.

“The most damaging phrase in the language is: ‘It’s always been done that way.’” Steve Kemp quotes Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, one of history’s unique incarnations who challenged perspectives of what, or who, should merit the term ‘elite’. Hopper – for the uninitiated – started out as a maths professor. Originally rejected by the US Navy in World War II she became an older naval reserve and a pioneer of computer programming, going on to be awarded one of the highest military ranks in America.

Steve is making two points in one. The first is that change is always desirable, always necessary. If we just do something one way because we always did it thus, then, as rear-admirals might say, we’re sunk. The second reveals British Fencing’s Head of Pathways dislike of inauthenticity, and those who claim to be something, or be offering something, that is not entirely honest.

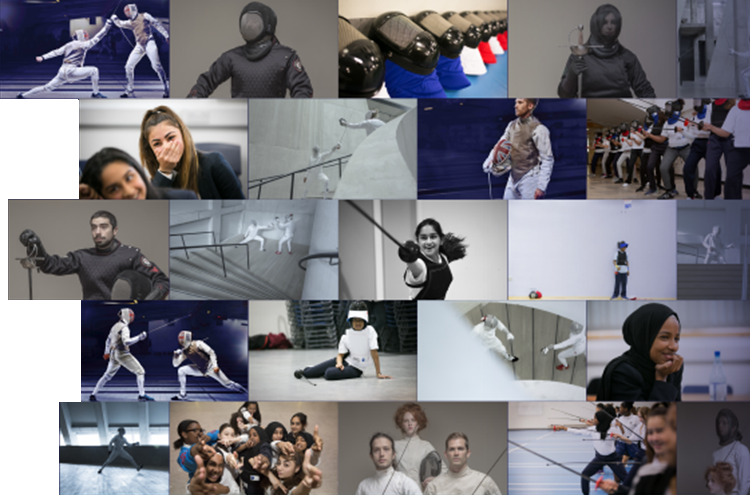

Elite, or ‘e-lite’ as Steve refers to it, paired with terms like ‘high-performance’ are what he calls ‘words on a wall’. He could be the British Fencing equivalent of Banksy – an unlikely iconoclast re-spraying the ramparts of our minds where we’ve stalled in our thinking. For him, the truly elite stand at the pinnacle of their disciplines. All sports have their elites too, and all sports also have those who do just want to take part at their local club, school, university or wherever, however takes their fancy. Every type of fencer has their merit.

The ADP recognises that. What essentially started out as a talent programme for those aged 15 to 23, has become the umbrella for a defined pathway – a track that starts at 14/15 years old and carries onto a fencer in their thirties. Steve analogises further, encouraging us to think of the fencing athlete’s journey – ultimately the Olympic goal – as akin to climbing Everest. Progressing through Cadet and Junior ranks is like flying from London to Kathmandu. The first major milestone of a World Championships is the same as reaching Base Camp 1. The climb is long and arduous. Many give up. 99% don’t make it anywhere near the top. The Hillary Steps? Well, Steve reckons, that’s like Marcus’ tenacity in pursuing and securing qualification for the Tokyo Games, coming within a whisper of the very summit.

Steve’s point is that what matters is the athlete’s journey. His responsibility is to lead a team who can create the kind of environment that will help the fencer to go as far as they can, as well as they can. When asked about criticisms and comparisons with other more ‘successful’ fencing nations than us, Steve makes the observation that GB as a country has just come fourth in the medal table in Tokyo. He also does a bit of a Banksy again, conjuring up a picture that, while it’s always the goal to strive towards, placing the aim of being global podium-perchers above all else might nonetheless prove to be at a devastating cost to athletes’ mental and physical healths. What’s more, 99% still wouldn’t make it anyway – that’s just the incontrovertible statistic of sport maths and medals. It’s easy to imagine how that ‘at all costs’ concept, as well as what we think we should wish for, could be aerosol-ed into visually arresting, thought-provoking graffiti art – at which point we may well reconsider.

Making the fencer experience worthwhile at whatever level is something Steve holds dear. He’s fully aware that no matter how strong you think you are, the athlete situation is already a pressured one. Factor in dealing with stress, loss, even trauma, and the development of people ramps up to the next level. Steve recounts a personally transformative experience of attending a training course where one day was dedicated to hostage-taking. Actors came in to play a scenario that was no child’s-play: delegates set up a firearms team, practiced to be ready to go in, if required, and the role of the negotiator was undertaken.

In this case, the context was a husband and wife. Just the two of them; the husband holding his wife hostage. Only she was pregnant, so now there were three lives at stake. The conversation with the husband was going well, trust was being developed. Then it transpired that the husband was a serving soldier who had just returned from Helmand. That one word triggered a massive emotional response. Steve said he was completely overwhelmed, and had to get up to leave the room for a while. Get his head back. Breathe. Why? “Suffering”, he replies. “The layers of suffering”. Seeing others endangered, even in a theoretical situation, appears to have reminded him of his own human vulnerability as well as prompting him to think of a former co-worker who had experienced a profound mental crisis. Distress and trauma are elements that are in ADP Programmes. Steve Kemp wants to make sure that when they happen – and they will happen – there is the psychologically safe environment to respond in these times, for fencers, and the team of coaches and support staff.

For those still holding fast to their ‘all or nothing’ ethos and the binaries of ‘do or die’, ‘win or lose’, Steve has a question, “Who would you rather have dinner with: Tiger Woods or Roger Federer?” He points to the former, agreeing the system of starting the individual from a really tender age on the golfing circuit works and gets results, but is rather like open-cast mining. You find your gold potentially having left a mound of disturbed earth in your wake. With Federer, the picture of a more fully-rounded athlete emerges. The multiple Grand Slam winner – as a young sportsman – also played basketball, badminton, table tennis, handball and football and he swam, wrestled, skated and skied. He didn’t settle on tennis until he was a teenager.

The beating heart of the ADP is firmly focussed on forming such well-rounded ‘better people’, and that’s done by using expertise and experience as well as deploying a collective ability to unify. Another crucial point is that the ADP is not mandatory. Steve emphasises that it’s a step that the athlete must take; it’s down to the fencer to show their commitment and make their decisions and own their responsibilities. Crucial because this push-and-pull of the development pendulum can prove to be a heavy burden for both sides. Steve knows that as much as his vision can propel fencers forth, the data might equally find points where his vision has held them back. “This has to be their journey, their moment in time. If I’m honoured, then I get to be part of that. The athletes can take away a bit of what I’ve done with them, or they can walk away if it’s not for them – either’s good because it’s their choice. It has to be.”

If anyone labours under the misunderstanding that, in creating a caring, sharing development pathway, Steve has lost sight of the real game then perhaps they should swipe through the photos of his 16 year-old daughter’s rower’s hands on his phone. Her palms are wrecked. Blistered, battered, bulbous – a sacrifice to the rigours of sport. But, as he all too well appreciates, she is growing and learning and interacting and taking responsibility – getting used to building up life skills of every kind and she’s putting herself – via her sport – into challenging contexts that she can use to develop into a better person.

Steve is clearly purposeful about what’s needed next in fencing: to become ‘world-class ready’ by 2023 in time for Paris 2024. “Who knows if it will happen but we’re creating that plan. We’re on the bus, on the journey. We’re going. It’s hard work and hard work works”. The ADP is constantly evolving because there’s constantly work being done and constantly more work to do. He sees himself not as the owner but as the caretaker of many a hope and dream. “I’m a custodian for a short amount of time. If I can leave it all in a better place then I can sit in my armchair when I’m old and feel ok”.

Throughout his interview, Steve weighs up every idea, references every motivational speaker and expert, every mode of thinking and processing – sometimes flipping things on their head, offering fresh and unusual angles. At one point he fishes out his notebook to show a flow-chart diagram-thingy he’s drafted. The cat’s out of the bag – he’s deffo not the real Banksy. Not with those pen strokes. Nevertheless he’s still the person brave enough to attempt change and then keep on driving it so our fencers can end up in a better place as better individuals.

“Yes”, he confirms. “I draw on everything, I try to put everybody else first. All good people should put themselves second”.

Points taken, Steve. But just don’t expect us to let you loose with a spray-can any time soon.

You can find more articles about coaching in our coach digest here.

Subscribe to the Fencing Digest, a weekly summary email featuring the previous week’s latest news and announcements. Sign up here.

Sign up to receive regular highlights from the exciting world of fencing - celebrating the best of our unique and inspiring community